Intro

Hello there!

Today we will explore SIMD instructions in .NET and how it can speed up your algorithms. It’s not a cover of all capabilities and definitely, it is not an “ultimate” guide on how to convert any algorithm to SIMD version but rather a report after playing with SIMD in .NET.

So, what is SIMD? I think it’s clear that the CPU executes operations from your program and can execute only one operation (to load something from memory, to add, to multiply, etc). If you need to process a lot of data, it could be pretty slow.

There is a “well-known” alternative to it - multi-threading. You can come up with another version of your algorithm optimized to multiple CPU threads. For example, you need to process an array then you can split it by some chunks and each thread will be responsible for its own work. In real life, you can’t scale each algorithm this way, sometimes you need to “invent” something completely different, or even worse, you can’t use multiple threads.

But there is another approach to improve the performance of your algorithm. SIMD:

Single instruction, multiple data is a type of parallel processing. There are simultaneous (parallel) computations, but each unit performs exactly the same instruction at any given moment (just with different data). SIMD is particularly applicable to common tasks such as adjusting the contrast in a digital image or adjusting the volume of digital audio. Most modern CPU designs include SIMD instructions to improve the performance of multimedia use.

Instead of adding one number to another one which will require processing each element of data one by one. SIMD allows you to process several numbers at once. For example, you want to multiply all values in the array (1, 2, 3, 4) by 2.

Task and Solution

As a test algorithm, I decided to choose image grayscale conversion. You have a colored (RGB) image as an input and you need to produce a grayscale version of this image. There is a simple formula to get a grayscale pixel:

0.299 * R + 0.587 * G + 0.114 * B

where R, G, B - are variables for corresponding color components.

So, the original test image is:

and the grayscale version:

It is simple enough to implement without any SIMD knowledge but, at the same time, it’s not a simple multiplication of two vectors and it will allow us to explore more SIMD instructions and pitfalls.

Linear Implementation

Let’s start from the baseline - the linear implementation without Multi-threading or SIMD instructions. It’s just a for loop over our pixel array. The pixel data is represented by 3 bytes (1 byte per RGB color component):

var result = new byte[pixels.Length];

for (var i = 0; i < result.Length; i += 3)

{

var gray = (byte)(0.299 * pixels[i] + 0.587 * pixels[i + 1] + 0.114 * pixels[i + 2]);

result[i] = gray;

result[i + 1] = gray;

result[i + 2] = gray;

}

return result;Multi-thread Implementation

The next version is a multi-threaded algorithm. It is the same as the previous one but instead, I replaced the for-loop with Parallel.For.

var result = new byte[pixels.Length];

Parallel.For(0, result.Length / 3, i =>

{

var gray = (byte)(0.299 * pixels[i * 3] + 0.587 * pixels[i * 3 + 1] + 0.114 * pixels[i * 3 + 2]);

result[i * 3] = gray;

result[i * 3 + 1] = gray;

result[i * 3 + 2] = gray;

});

return result;Ok, so far, everything looks pretty simple.

SSE

Ok, the SSE algorithm wouldn’t be so easy. SSE instructions are based on 128-bit vectors. So, the first thing we need to resolve how we need to pack our pixels into these vectors. 128 bits is equal to 16 bytes. It means we can process 16 bytes at once but unfortunately, we only can pack 5 pixels into one vector (5 * 3 bytes per pixel = 15) and “waste” one byte: var v = Vector128.Create(pixels, i).

The next thing is how can we apply our coefficients. We need to multiply a correct number to the correct color component and because we are working with SIMD, you might think about creating another vector var k = Vector128.Create(0.299f, 0.587f, 0.114f) and multiply our pixels by it. Unfortunately, it won’t work. First of all, a 128-bit vector could hold 4 floats (each float is a 32-bit number) but we are using only 3. The second problem is the data type mismatch. Our pixels vector is represented by 16 bytes but we are trying to multiply it by 4 floats. So, the easiest approach to solve this problem is to convert our pixels to floats, multiply them, and convert them back to bytes. Yeah, it sounds pretty easy but really it is not. For example, var v = Vector128.Create((float)pixels[i], (float)pixels[i + 1], (float)pixels[i + 2], (float)pixels[i + 3]) but such straight forward will be too slow. We are reading each array element one by one. It is faster to read a block of memory to a SIMD vector directly.

We could use a slightly different approach and pack each color component into a separate SIMD vector. Luckily, we have enough pixels in our byte vector. So, the byte vector has 5 full pixels and we could try to convert them to 3 vectors for R, G, and B colors (each one will be represented by 4 floats). This way, we could easily multiply them by our coefficients but it increases the amount of “wasted” data. 3 float vectors are equal to 12 bytes. So, now a quarter of the original 16-byte vector is not needed. To implement this idea, we need to use several SSE instructions: Shuffle, UnpackLow, UnpackHigh, ConvertToVector128Single.

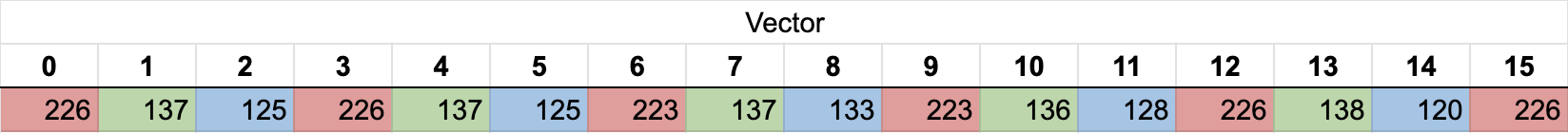

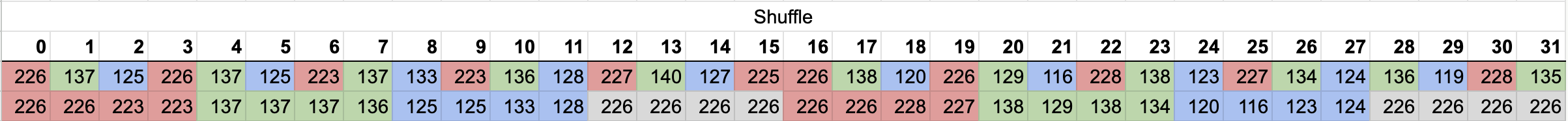

Shuffle has a self-explanatory name. It shuffles bytes in your vector in a specified order. For example, we have a vector:

Note: each color component is marked by its respective color. Gray means that this pixel is not used.

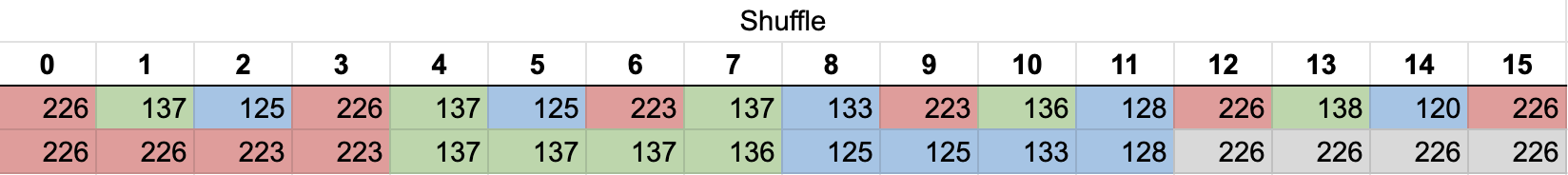

and we want to store all color components together, eg. all Rs, all Gs, and Bs. We can use the Shuffle method for this with the following mask:

var mask = Vector128.Create(new byte[]

{

0, 3, 6, 9,

1, 4, 7, 10,

2, 5, 8, 11,

0, 0, 0, 0

});

var v = Vector128.Create(pixels, i);

var planar = Ssse3.Shuffle(v, mask);The Shuffle method uses the mask vector as a list of indexes from the original vector and planar will contain:

Note: The first vector has original values. And the second one is the reshuffled one.

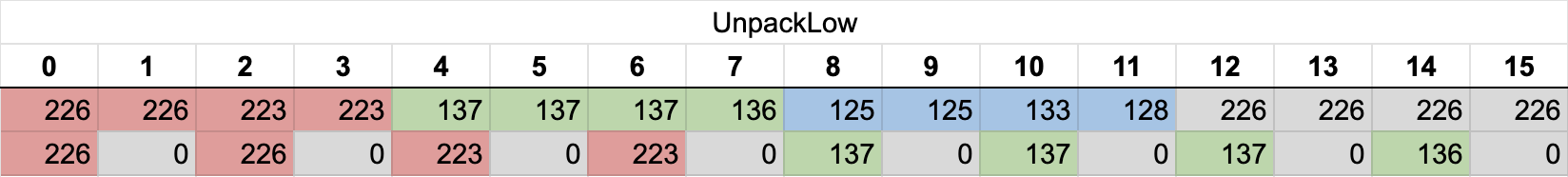

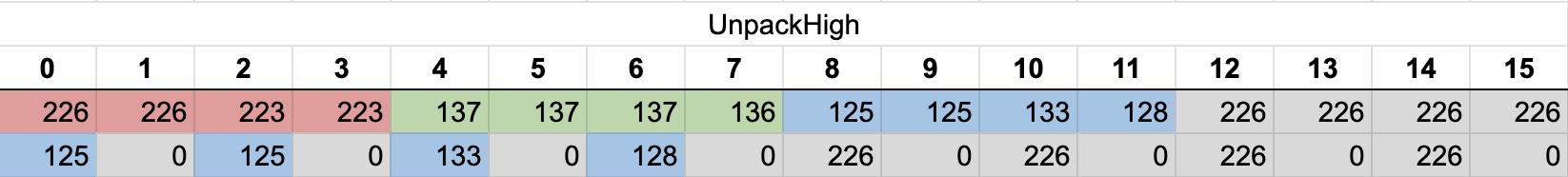

Now, our pixel data has a better representation because we can easily split it into several vectors for each component by using UnpackLow/UnpackHigh. The UnpackLow method takes a lower part of the vector and extracts it into a new vector. By executing it once on the reshuffled vector, we can extract a new vector with R and G components:

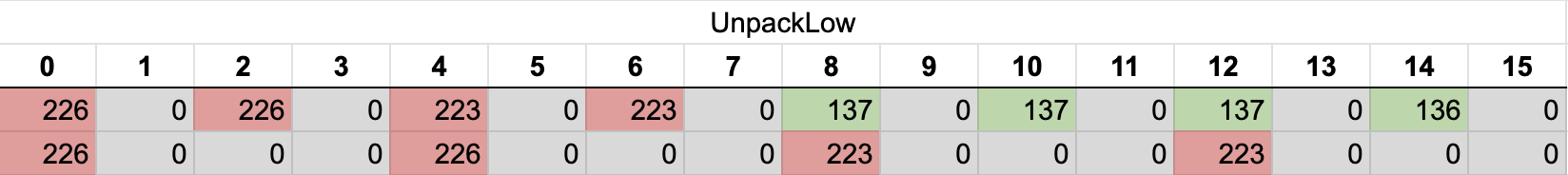

Then we need to execute it again to extract only the R component:

The UnpackHigh method works the same way but it extracts the high part of the vector:

After all these manipulations, we’ll have 3 vectors for each component and only one last part is left - to convert them into float vectors. We can use the ConvertToVector128Single method. So, the final part of the code will look like this:

var v = Vector128.Create(pixels, i);

var planar = Ssse3.Shuffle(v, mask);

var l = Sse2.UnpackLow(planar, Vector128<byte>.Zero);

var r = Sse2.UnpackLow(l, Vector128<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var rf = Sse2.ConvertToVector128Single(r);

var g = Sse2.UnpackHigh(l, Vector128<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var gf = Sse2.ConvertToVector128Single(g);

var h = Sse2.UnpackHigh(planar, Vector128<byte>.Zero);

var b = Sse2.UnpackLow(h, Vector128<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var bf = Sse2.ConvertToVector128Single(b);So, we almost finished our SSE algorithm, with only two last steps left. We need to calculate a gray color and save it into a result array. We could use Sse.Multiply and Sse.Add to multiply color components by coefficients and then add them together and it would work. But there is a fused multiply add method - Fma.MultiplyAdd. It does multiplication and addition at the same time - perfect for our case:

var rk = Vector128.Create(0.299f);

var gk = Vector128.Create(0.587f);

var bk = Vector128.Create(0.114f);

var gray = Fma.MultiplyAdd(

rf, rk,

Fma.MultiplyAdd(

gf, gk,

Sse.Multiply(bf, bk)

)

);And the last thing is to convert floats back into bytes and reshuffle them into the correct order (the grayb vector stores 4 gray pixels but to support the same pixel format as in the input array, we need to repeat each gray pixel 3 times):

var grayb = Sse2.ConvertToVector128Int32(gray).AsByte();

var grayMask = Vector128.Create(new byte[]

{

0, 0, 0,

4, 4, 4,

8, 8, 8,

12, 12, 12,

0, 0, 0, 0

});

var grayShuffled = Ssse3.Shuffle(grayb, grayMask);

grayShuffled.CopyTo(result, i);Last small point to note. In the final version of the SSE algorithm, you can see that we are allocating more bytes for grayscale images than we need: var result = new byte[pixels.Length + 16]. It is a workaround to allow to use vector’s CopyTo method directly. We are reading data by 16 bytes blocks but unfortunately, we process only 12 bytes. So, each time we need to store grayscale pixels back to the array, we need to save 12 bytes but SSE doesn’t support “partial” save. Instead, we could allocate a bigger array to account for all possible unnecessary bytes and then ignore them. Yes, as an alternative, we could create stack allocated array (stackalloc byte[16]), save vector there, slice it, and then store only 12 bytes. But it would result in significant performance loss.

Also, at the end of the SSE algorithm, you can see a copy of the linear grayscale algorithm. We need to add to handle edge cases. SSE processes data by block but what if our data array doesn’t have the exact amount of blocks, for example, 35 bytes. We still need to process these last pixels and we know that the amount of these pixels will be smaller than the block size (16 bytes). So, we don’t need to process such a small amount of data by SSE but instead, the linear algorithm will be enough.

Here is the full code for the SSE algorithm:

Final SSE version

var result = new byte[pixels.Length + 16];

var mask = Vector128.Create(new byte[]

{

0, 3, 6, 9,

1, 4, 7, 10,

2, 5, 8, 11,

0, 0, 0, 0

});

var grayMask = Vector128.Create(new byte[]

{

0, 0, 0,

4, 4, 4,

8, 8, 8,

12, 12, 12,

0, 0, 0, 0

});

var rk = Vector128.Create(0.299f);

var gk = Vector128.Create(0.587f);

var bk = Vector128.Create(0.114f);

var i = 0;

for (; pixels.Length - i >= 16; i += 12)

{

var v = Vector128.Create(pixels, i);

var planar = Ssse3.Shuffle(v, mask);

var l = Sse2.UnpackLow(planar, Vector128<byte>.Zero);

var r = Sse2.UnpackLow(l, Vector128<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var rf = Sse2.ConvertToVector128Single(r);

var g = Sse2.UnpackHigh(l, Vector128<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var gf = Sse2.ConvertToVector128Single(g);

var h = Sse2.UnpackHigh(planar, Vector128<byte>.Zero);

var b = Sse2.UnpackLow(h, Vector128<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var bf = Sse2.ConvertToVector128Single(b);

var gray = Fma.MultiplyAdd(

rf, rk,

Fma.MultiplyAdd(

gf, gk,

Sse.Multiply(bf, bk)

)

);

var grayb = Sse2.ConvertToVector128Int32(gray).AsByte();

var grayShuffled = Ssse3.Shuffle(grayb, grayMask);

grayShuffled.CopyTo(result, i);

}

for (; i < pixels.Length; i += 3)

{

var gray = (byte)(0.299 * pixels[i] + 0.587 * pixels[i + 1] + 0.114 * pixels[i + 2]);

result[i] = gray;

result[i + 1] = gray;

result[i + 2] = gray;

}

return (result, pixels.Length);AVX

There are several versions of SSE (SSE, SSE2, and so on) and each version adds new methods, and new complex instructions to process data. But they are all based on 128-bit vectors (the size of CPU registers to store data for SSE instructions). So, at some point, CPU engineers introduced a new set of instructions - AVX. You can think about it as SSE but on 256-bit vectors. AVX has a lot of similar instructions as SSE but also adds some new ones.

In this section, we will take a look at the AVX algorithm. It will be based on the SSE version with the same small fixes because some AVX methods don’t work as you expect.

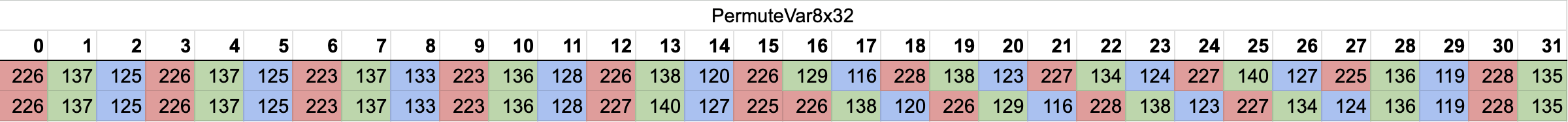

First of all, we need to take a look at the Shuffle method. We expect it to shuffle the entire 256-bit vector but unfortunately, it doesn’t work this way. Avx2.Shuffle processes one 256-bit vector as it is two 128-bit vectors (they are called lanes). So, you can shuffle bytes within a lane but you can’t shuffle bytes across lanes. To solve this problem, we need to add one additional operation - Avx2.PermuteVar8x32. It treats 256-bit vectors as 8 32-bit integers and allows to shuffle them in any order.

But it doesn’t produce the final result. We still need to use shuffle to get color components in the right order:

var perm = Vector256.Create(0, 1, 2, 6, 3, 4, 5, 7);

var mask = Vector256.Create(new byte[]

{

0, 3, 6, 9,

1, 4, 7, 10,

2, 5, 8, 11,

0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 3, 6, 9,

1, 4, 7, 10,

2, 5, 8, 11,

0, 0, 0, 0,

});

var v = Vector256.Create(pixels, i);

v = Avx2.PermuteVar8x32(v.AsInt32(), perm).AsByte();

var planar = Avx2.Shuffle(v, mask);Also, we need to do the same at the end of our algorithm to get gray pixels.

Final AVX version

var result = new byte[pixels.Length + 32];

var perm = Vector256.Create(0, 1, 2, 6, 3, 4, 5, 7);

var mask = Vector256.Create(new byte[]

{

0, 3, 6, 9,

1, 4, 7, 10,

2, 5, 8, 11,

0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 3, 6, 9,

1, 4, 7, 10,

2, 5, 8, 11,

0, 0, 0, 0,

});

var grayMask = Vector256.Create(new byte[]

{

0, 0, 0,

4, 4, 4,

8, 8, 8,

12, 12, 12,

0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0,

4, 4, 4,

8, 8, 8,

12, 12, 12,

0, 0, 0, 0,

});

var grayPerm = Vector256.Create(0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 3, 7);

var rk = Vector256.Create(0.299f);

var gk = Vector256.Create(0.587f);

var bk = Vector256.Create(0.114f);

var i = 0;

for (; pixels.Length - i >= 32; i += 24)

{

var v = Vector256.Create(pixels, i);

v = Avx2.PermuteVar8x32(v.AsInt32(), perm).AsByte();

var planar = Avx2.Shuffle(v, mask);

var l = Avx2.UnpackLow(planar, Vector256<byte>.Zero);

var r = Avx2.UnpackLow(l, Vector256<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var rf = Avx.ConvertToVector256Single(r);

var g = Avx2.UnpackHigh(l, Vector256<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var gf = Avx.ConvertToVector256Single(g);

var h = Avx2.UnpackHigh(planar, Vector256<byte>.Zero);

var b = Avx2.UnpackLow(h, Vector256<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var bf = Avx.ConvertToVector256Single(b);

var gray = Fma.MultiplyAdd(

rf, rk,

Fma.MultiplyAdd(

gf, gk,

Avx.Multiply(bf, bk)

)

);

var grayb = Avx.ConvertToVector256Int32(gray).AsByte();

var grayShuffled = Avx2.Shuffle(grayb, grayMask);

grayShuffled = Avx2.PermuteVar8x32(grayShuffled.AsInt32(), grayPerm).AsByte();

grayShuffled.CopyTo(result, i);

}

for (; i < pixels.Length; i += 3)

{

var gray = (byte)(0.299 * pixels[i] + 0.587 * pixels[i + 1] + 0.114 * pixels[i + 2]);

result[i] = gray;

result[i + 1] = gray;

result[i + 2] = gray;

}

return (result, pixels.Length);Benchmark results

// BenchmarkDotNet v0.14.0

// Runtime=.NET 9.0.1 (9.0.124.61010), X64 RyuJIT AVX2

// GC=Concurrent Workstation

// HardwareIntrinsics=AVX2,AES,BMI1,BMI2,FMA,LZCNT,PCLMUL,POPCNT,AvxVnni,SERIALIZE VectorSize=256

// Job: MediumRun(IterationCount=15, LaunchCount=2, WarmupCount=10)

BenchmarkDotNet v0.14.0

12th Gen Intel Core i7-12700K, 1 CPU, 20 logical and 12 physical cores

.NET SDK 9.0.102

[Host] : .NET 9.0.1 (9.0.124.61010), X64 RyuJIT AVX2

MediumRun : .NET 9.0.1 (9.0.124.61010), X64 RyuJIT AVX2

Job=MediumRun Toolchain=.NET 9.0 IterationCount=15

LaunchCount=2 WarmupCount=10

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LinearTest | 615.76 μs | 3.947 μs | 5.907 μs | 1.00 |

| ParallelTest | 228.74 μs | 4.631 μs | 6.641 μs | 0.37 |

| SseTest | 133.07 μs | 1.304 μs | 1.951 μs | 0.22 |

| AvxTest | 94.35 μs | 0.936 μs | 1.401 μs | 0.15 |

As you can see, we can get about 6 times better performance by using AVX instructions without using multiple threads. Yeah, we need to create more complex code and handle a lot of edge cases. For example, in the real image processing library, we need to check the support of specific instructions and fallback linear implementation if they are not supported. Also, we need to support ARM and other platforms. But for some applications, these complications are worth it.

Here is the full code for the benchmark GitHub.

Program.cs

using System.Runtime.Intrinsics;

using System.Runtime.Intrinsics.X86;

using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes;

using BenchmarkDotNet.Configs;

using BenchmarkDotNet.Jobs;

using BenchmarkDotNet.Running;

using BenchmarkDotNet.Toolchains.CsProj;

using SixLabors.ImageSharp;

using SixLabors.ImageSharp.PixelFormats;

// var b = new GrayscaleBenchmark();

// b.Setup();

// var (result, length) = b.AvxTest();

// Image.LoadPixelData<Rgb24>(result.AsSpan(0, length), 512, 512).SaveAsPng("LennaGray.png");

if (args is null || args.Length == 0)

args = ["--filter", "*"];

BenchmarkSwitcher

.FromAssembly(typeof(Program).Assembly)

.Run(args,

ManualConfig.Create(DefaultConfig.Instance)

.AddJob(Job.MediumRun

.WithToolchain(CsProjCoreToolchain.NetCoreApp90))

.StopOnFirstError());

public class GrayscaleBenchmark

{

private byte[] pixels;

[GlobalSetup]

public void Setup()

{

var image = Image.Load<Rgb24>("Lenna.png");

pixels = new byte[image.Width * image.Height * (image.PixelType.BitsPerPixel / 8)];

image.CopyPixelDataTo(pixels);

}

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public (byte[], int) LinearTest()

{

var result = new byte[pixels.Length];

for (var i = 0; i < result.Length; i += 3)

{

var gray = (byte)(0.299 * pixels[i] + 0.587 * pixels[i + 1] + 0.114 * pixels[i + 2]);

result[i] = gray;

result[i + 1] = gray;

result[i + 2] = gray;

}

return (result, result.Length);

}

[Benchmark]

public (byte[], int) ParallelTest()

{

var result = new byte[pixels.Length];

Parallel.For(0, result.Length / 3, i =>

{

var gray = (byte)(0.299 * pixels[i * 3] + 0.587 * pixels[i * 3 + 1] + 0.114 * pixels[i * 3 + 2]);

result[i * 3] = gray;

result[i * 3 + 1] = gray;

result[i * 3 + 2] = gray;

});

return (result, result.Length);

}

[Benchmark]

public (byte[], int) SseTest()

{

if (!Sse42.IsSupported)

throw new Exception();

var result = new byte[pixels.Length + 16];

var mask = Vector128.Create(new byte[]

{

0, 3, 6, 9,

1, 4, 7, 10,

2, 5, 8, 11,

0, 0, 0, 0

});

var grayMask = Vector128.Create(new byte[]

{

0, 0, 0,

4, 4, 4,

8, 8, 8,

12, 12, 12,

0, 0, 0, 0

});

var rk = Vector128.Create(0.299f);

var gk = Vector128.Create(0.587f);

var bk = Vector128.Create(0.114f);

var i = 0;

for (; pixels.Length - i >= 16; i += 12)

{

var v = Vector128.Create(pixels, i);

var planar = Ssse3.Shuffle(v, mask);

var l = Sse2.UnpackLow(planar, Vector128<byte>.Zero);

var r = Sse2.UnpackLow(l, Vector128<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var rf = Sse2.ConvertToVector128Single(r);

var g = Sse2.UnpackHigh(l, Vector128<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var gf = Sse2.ConvertToVector128Single(g);

var h = Sse2.UnpackHigh(planar, Vector128<byte>.Zero);

var b = Sse2.UnpackLow(h, Vector128<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var bf = Sse2.ConvertToVector128Single(b);

var gray = Fma.MultiplyAdd(

rf, rk,

Fma.MultiplyAdd(

gf, gk,

Sse.Multiply(bf, bk)

)

);

var grayb = Sse2.ConvertToVector128Int32(gray).AsByte();

var grayShuffled = Ssse3.Shuffle(grayb, grayMask);

grayShuffled.CopyTo(result, i);

}

for (; i < pixels.Length; i += 3)

{

var gray = (byte)(0.299 * pixels[i] + 0.587 * pixels[i + 1] + 0.114 * pixels[i + 2]);

result[i] = gray;

result[i + 1] = gray;

result[i + 2] = gray;

}

return (result, pixels.Length);

}

[Benchmark]

public (byte[], int) AvxTest()

{

if (!Avx2.IsSupported)

throw new Exception();

var result = new byte[pixels.Length + 32];

var perm = Vector256.Create(0, 1, 2, 6, 3, 4, 5, 7);

var mask = Vector256.Create(new byte[]

{

0, 3, 6, 9,

1, 4, 7, 10,

2, 5, 8, 11,

0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 3, 6, 9,

1, 4, 7, 10,

2, 5, 8, 11,

0, 0, 0, 0,

});

var grayMask = Vector256.Create(new byte[]

{

0, 0, 0,

4, 4, 4,

8, 8, 8,

12, 12, 12,

0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0,

4, 4, 4,

8, 8, 8,

12, 12, 12,

0, 0, 0, 0,

});

var grayPerm = Vector256.Create(0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 3, 7);

var rk = Vector256.Create(0.299f);

var gk = Vector256.Create(0.587f);

var bk = Vector256.Create(0.114f);

var i = 0;

for (; pixels.Length - i >= 32; i += 24)

{

var v = Vector256.Create(pixels, i);

v = Avx2.PermuteVar8x32(v.AsInt32(), perm).AsByte();

var planar = Avx2.Shuffle(v, mask);

var l = Avx2.UnpackLow(planar, Vector256<byte>.Zero);

var r = Avx2.UnpackLow(l, Vector256<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var rf = Avx.ConvertToVector256Single(r);

var g = Avx2.UnpackHigh(l, Vector256<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var gf = Avx.ConvertToVector256Single(g);

var h = Avx2.UnpackHigh(planar, Vector256<byte>.Zero);

var b = Avx2.UnpackLow(h, Vector256<byte>.Zero).AsInt32();

var bf = Avx.ConvertToVector256Single(b);

var gray = Fma.MultiplyAdd(

rf, rk,

Fma.MultiplyAdd(

gf, gk,

Avx.Multiply(bf, bk)

)

);

var grayb = Avx.ConvertToVector256Int32(gray).AsByte();

var grayShuffled = Avx2.Shuffle(grayb, grayMask);

grayShuffled = Avx2.PermuteVar8x32(grayShuffled.AsInt32(), grayPerm).AsByte();

grayShuffled.CopyTo(result, i);

}

for (; i < pixels.Length; i += 3)

{

var gray = (byte)(0.299 * pixels[i] + 0.587 * pixels[i + 1] + 0.114 * pixels[i + 2]);

result[i] = gray;

result[i + 1] = gray;

result[i + 2] = gray;

}

return (result, pixels.Length);

}

}Points to improve

There are some points to improve the algorithms. The first and the obvious one is to use all available bits in the vector. Right now, we are using 75% of a vector size (12 of 16 bytes for SSE and 24 of 32 bytes for AVX). It is just a waste. It would be easier if the pixels (RGB) array is preprocessed to separate color components. So, we would be able to create a vector for each color and multiply it by a coefficient.

Another point is to replace Vector128.Create/Vector256.Create by unsafe code or the Unsafe class:

var arr = ...;

ref var v = ref Unsafe.As<int, Vector128<int>>(ref MemoryMarshal.GetArrayDataReference(arr));

// ...

for (...)

{

v = ref Unsafe.Add(ref v, 1);

// ...

}Unsafe.As asks the runtime to treat a reference of one type by another type. So, we are “casting” an array into a vector. Unsafe.Add moves the pointer by a specified amount (basically the same way as pointer arithmetics in C++). I haven’t checked but this code could be a little bit faster.

Conclusion

SIMD instructions (SSE/AVX) can significantly accelerate computationally intensive tasks like image processing, resulting in impressive performance improvements. While the implementation of SIMD in .NET requires a deeper understanding of vectorization and low-level CPU instructions, the benefits in speed and efficiency are clear, especially in applications where performance is critical. Future optimizations, such as better utilization of vector space and leveraging unsafe code, could further enhance SIMD’s potential. These techniques offer a valuable toolset for developers seeking high-performance solutions.